Distilled: Binary Search

Binary search is one of the classic algorithms in computer science, with its first implementation dating back to somewhere in the 1940s or 1950s. It solves the problem of finding a number in a sorted list and manages to do so quite efficiently. It is one of the examples where we can use a problem constraint or characteristic to our advantage: if the list wasn’t sorted, we wouldn’t be able to use binary search and would have to settle with a different, maybe slower solution.

That being said, this algorithm is notoriously tricky to implement, being recognized by Donald Knuth as such. In this article we’ll explore the core idea of binary search and understand its implementation in a way where no +/-1 is left unturned.

The basic principle

The main idea of binary search is to eliminate half of the search space at each step. You do this repeatedly until you find what you’re looking for or run out of places to search.

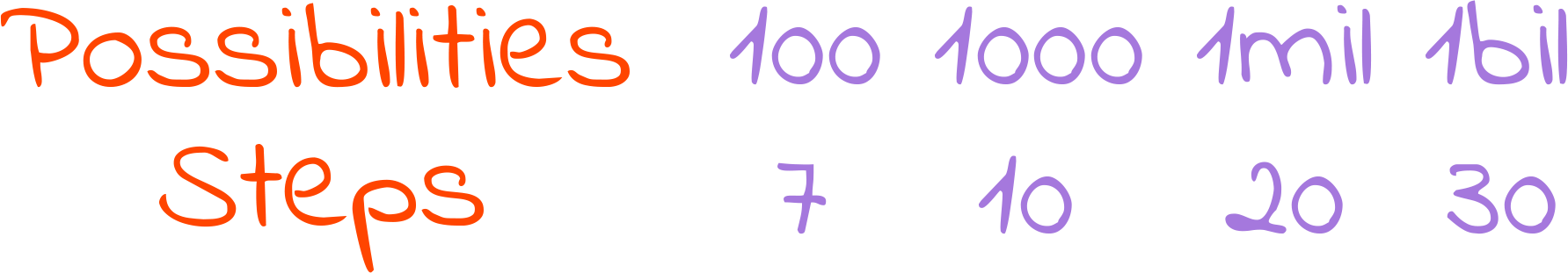

What maybe isn’t obvious at first glance, and the reason binary search is considered fast is that in order for it to run one extra step, you would have to double the number of things it has to consider. So, if it takes 3 steps to search among 8 possibilities, searching among 16 would take 4: in one step we discard half of the possibilities (8), and then we know that searching the other half (8) takes 3 steps.

This translates to being able to search 1000000000 possibilities with just 30 steps, and computers can execute 30 steps in no time at all.

This whole process only works because of the constraint imposed by our problem: we are working with a group of numbers that is sorted. In this setting, we can “eliminate half of the search space” by looking at the number in the middle. This number is our reference: half of the search space is smaller than the reference, and the other half is bigger. Comparing the thing we are looking for with our reference, we can find out which half we are supposed to discard:

- If we want to find something bigger than the reference, we discard the things that are smaller than the reference

- If we want to find something smaller than the reference, we discard the things that are bigger than the reference

- If it is neither bigger nor smaller, the reference is what we are looking for

This leads us to the classic binary search implementation (more verbose than necessary for clarity purposes). Along with all the pieces of code in this article, it is written in Python, but the language of choice is mostly irrelevant.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def binary_search(numbers, target):

start = 0

end = len(numbers)

while start < end:

distance = end - start

mid = start + distance // 2

if target == numbers[mid]:

return mid

elif target > numbers[mid]:

start = mid + 1

elif target < numbers[mid]:

end = mid

return -1

The classic in-depth

1

def binary_search(numbers, target):

We start with our function definition. Here numbers is a list of numbers in ascending order (from smallest to biggest), and target is the number we want to find in the list. This implementation will return the index where target is located in the list, or -1 if it isn’t present.

1

2

start = 0

end = len(numbers)

We use two variables, start and end, to delimit our search space. These variables hold indexes of the elements in the list, and they represent a range initially encompassing all the numbers. The index start is included in the range, and the index end isn’t (recall that Python is 0-indexed, so len(numbers) is “after” the last element). When binary search cuts the search space in half, it will do so by changing these indexes. One cut in half is done by either increasing start or decreasing end.

1

2

3

while start < end:

...

return -1

This is our loop, where most of the work will be done, and where we put our loop condition. One of the ways the search ends is when we run out of places to search, and in this case our code exits the loop and returns the value -1. We can identify this situation by comparing the edges of our interval.

Along the execution of the algorithm, start will increase or remain unchanged and end will decrease or remain unchanged, as our interval constantly shrinks by getting cut in half. At some point, end may decrease so much it ends up with a value smaller than the value of start. Something similar can happen with start increasing and becoming bigger than end. These situations indicate that there is nothing left to search, as our interval edges make no sense. Those things happen when start >= end, so while start < end, we can keep searching.

The case where start and end have the same value represents an empty search space, and we break the while condition, exiting the loop. That’s because end will always have an index that we are not interested in (we guarantee that in the initialization, and make sure that it still holds later on), while start will have an index that we are not sure if it could be our target. So when they have the same value, i.e.: 4, start says the target could be in 4, and end says the target is definitely not in 4. We trust end and get out of the loop.

1

2

distance = end - start

mid = start + distance // 2

This piece of code in the while loop is responsible for calculating the half point of the search space. The half point is where our reference is located. Initially, we find out how far apart the start and end indexes are (in distance), then we go from start and walk half of distance to reach the mid point.

As we are working with indexes (i.e. mid indicates the index of the element in the middle of the search space), and indexes have to be whole numbers, we use Python’s floor division operator //, as it rounds the result of the division down to the nearest integer. This procedure gives the mid calculation the interesting property that start <= mid < end, as long as start < end (which always happens inside the while loop, as it is the loop condition). This follows from two observations:

- Inside our loop, we have that

start < end, which translates ondistancealways being greater than zero.distance // 2however, is a different story, as the floor division makes1 // 2 = 0, sodistance // 2can be0. Then, as mid is calculated by adding something greater than or equal to0tostart, we have thatstart <= mid - As we are rounding down,

distance // 2is never equal todistance, it is always smaller (if we were rounding up it could be equal i.e.:1/2rounded up =1). This translates intomidalways being smaller thanend, becauseend = start + distanceandmid = start + distance // 2. Therefore, we have thatmid < end

1

2

3

4

5

6

if target == numbers[mid]:

return mid

elif target > numbers[mid]:

start = mid + 1

elif target < numbers[mid]:

end = mid

This snippet contains the logic for cutting our search interval in half, and to help us do that, we’ll use what we just discussed: the fact that after the mid calculation, start <= mid < end. We start comparing our reference (numbers[mid]) with the thing we are looking for (target):

- If our reference is equal to what we are looking for, it means we’ve found it, so we return its index,

mid If we are looking for something bigger than the reference, we eliminate the part of the search space that is smaller than the reference by increasing the variable

starttomid + 1. This is the first cut of the Shrinking Interval GIF.I say increase, because

midis, at the lowest, equal tostart, so adding one guarantees something bigger. The plus one also excludes the reference’s location(mid) from the updated search space, and we can safely do so because we verified thatnumbers[mid]isn’t equal to ourtarget, so we don’t search there anymore.Forgetting the

+ 1here can make the program get stuck in an infinite loop whenmidandstartare equal, asstartdoesn’t increase andmidnever gets removed from the search spaceIf we are looking for something smaller than the reference, we eliminate the part of the search space that is bigger than the reference by decreasing the variable

endtomid. This is the second cut of the Shrinking Interval GIF.Recall that

midis always smaller thanend, and thatenddenotes an index that is not included in the search space. That’s why here we don’t need the a- 1

This cycle of calculating mid, comparing the reference with the target and updating the limits of the search space is repeated each iteration of the loop until we either find what we’re looking for (reach the return mid line) or we have nowhere left to search and break the while condition, reaching the return -1 line.

Variations

There are many ways to implement binary search similar to what was shown above, but not quite the same. We’ll now take a look at some variations (again more verbose than necessary, for clarity purposes) and how they differ when compared to the one we’ve seen.

Both edges included (+1/-1 version)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def binary_search_both_edges(numbers, target):

start = 0

end = len(numbers) - 1

while start <= end:

distance = end - start

mid = start + distance // 2

if target == numbers[mid]:

return mid

elif target > numbers[mid]:

start = mid + 1

elif target < numbers[mid]:

end = mid - 1

return -1

This is probably the most popular one. The key difference here is that both edges of our interval, start and end, are included in the search space, so instead of holding an index we are not interested in, end now holds an index we may be interested in.

To account for that change, the while condition is slightly different: we now have to keep searching even if start is equal to end, as none of them indicates with certainty if an index should be considered or discarded. This change in the loop condition alters the mid calculation property from start <= mid < end to start <= mid <= end, as when end == start, distance and distance // 2 equal 0, making mid == start == end.

Doing end = mid like we did before would result in our program getting stuck when end and mid are equal. To solve that we assign mid - 1 to end, removing mid from the search space and guaranteeing that end always decreases.

No edges included (no +1/-1 version)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def binary_search_no_edges(numbers, target):

start = -1

end = len(numbers)

while start + 1 < end:

distance = end - start

mid = start + distance // 2

if target == numbers[mid]:

return mid

elif target > numbers[mid]:

start = mid

elif target < numbers[mid]:

end = mid

return -1

This version is cursed. Here, neither start nor end are included in the search space, so differently from the other versions, where the search space initially becomes empty when our variables are “crossed” (start > end) or equal (start == end), this one becomes empty when they are “side by side” (i.e.: start = 4 and end = 5).

Now our loop condition has to reflect the “while start and end are not crossed, equal or side by side” thing. However this cursed statement translates somewhat well to the idea of “even if I add something to start, it doesn’t reach end”, giving us start + 1 < end. This changes the mid calculation property to start < mid < end. The key to understand this is to realize that this new condition makes distance always greater than 1 (if it was 1, start and end would be side-by-side), which makes distance // 2 always greater than 0, which means mid is always greater than start. Remember that we are only dealing with whole numbers here.

This property allows us to adjust the edges of the interval in a clean way that still guarantees that start (end) always increases (decreases) and that mid is always removed from the search space. The price we pay is the cursed initialization of start with a negative number and the non-intuitive loop condition.

Recursion

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

def binary_search_recursion(numbers, target, start, end):

if start >= end:

return -1

distance = end - start

mid = start + distance // 2

if target == numbers[mid]:

return mid

elif target > numbers[mid]:

return binary_search_recursion(numbers, target, mid + 1, end)

elif target < numbers[mid]:

return binary_search_recursion(numbers, target, start, mid)

Not a big fan of recursion, but here is the classic version implemented with it. I won’t get into too much detail on this one, but the main question changes from “what condition allows me to keep searching?” to “what condition makes me stop?”, and the answer is the condition that previously broke the while loop, a.k.a edges crossed or equal: in this case the search ends and returns -1.

Each iteration of the loop becomes a new call to the function in the recursive version, and as we updated our search space at each iteration, we have to alter our function to receive an updated search space at each call, so now instead of receiving only a sorted list of numbers and a target, we take the edges of the interval as well.

The last thing that changes is the initialization of our interval, which could be done in different ways, but here I opted for a simple one, that is to let whoever calls the function choose the initial values for start and end. If you’re gonna use it, you’ll probably have to make something like this to guarantee the correct initialization:

1

2

def binary_search(numbers, target):

return binary_search_recursion(numbers, target, 0, len(numbers))

Mid calculation

1

2

3

mid = (start + end) // 2

# or

mid = start + (end - start) // 2

These are just some other ways to calculate mid that you might find. Both still use the floor division operator (//) as indexes are whole numbers. The first one is pretty intuitive: the middle point of two numbers is just their arithmetic mean. The second one is the same as what we saw in the classic version, but here no distance variable is created. If you opt for the first, overflow may be a concern in some languages, but in Python you’re safe. In general, the second is preferred.

Illegal loop condition

1

2

3

while start != end:

...

return -1

If the implementation with no edges included is cursed, using this loop condition in the classic one is illegal, but surprisingly, it works. Earlier in the article article I said that start (end) may increase (decrease) to the point of becoming bigger (smaller) than end (start), but that actually never happens in the classic version. They at most become equal, but never “cross”. Analyzing the mid calculation property (start <= mid < end), we can see why that is:

- Let’s assume that updating

startwithmid + 1(as we do in the classic version) makes it greater thanend. From the property, we know thatmid < end. Ifupdated_startnow exceedsend, we have thatmid < end < updated_start. However,updated_startismid + 1, so that statement implies thatendis a whole number that lies between another number and its successor, but that cannot happen (i.e.: there can be no whole number between5and6). - Now let’s assume that updating

endwithmid(as we do in the classic version) makes it less thanstart. From the property, we have thatstart <= mid. Ifupdated_endis now smaller thanstart, we have thatupdated_end < start <= mid. However,updated_endismid, so that statement implies thatstartis a number that is greater thanmidand at the same time is less than or equal tomid, which doesn’t make any sense.

If the loop ended, it was because start and end eventually became equal, that’s why while start != end still works. That being said, don’t do that. If the loop condition is changed, all of the analysis we did earlier becomes invalid, and we have no more guarantees about anything.

Conclusion

I hope this article helped you understand binary search a little bit better. If you are in doubt if a particular implementation is correct or not, start by looking at the search interval, and identify if it includes one, both or no edges. From the search interval you can derive the loop condition by thinking of cases where the edges would represent a valid or an empty search space. Then, when it’s time to update the edges, recall that the small one always increases, the big one always decreases and if your edge is included in the search space, you can’t update it to mid, so you’ll need a +/-1.